When Fewer Children Carry More History

This morning I noticed something small and oddly persistent. I passed by a playground on my way to run an errand. The swings were still. Not abandoned. Just unused. A few blocks later, a pharmacy was crowded, lines forming patiently, no urgency in the air. Nobody complained. Everyone seemed to know how long things take now.

It wasn’t dramatic. No alarm bells. Just a quiet imbalance that didn’t ask for permission to exist. That’s usually how structural changes arrive. They don’t knock. They rearrange the furniture while you’re busy elsewhere.

What the Age Pyramid Used to Mean

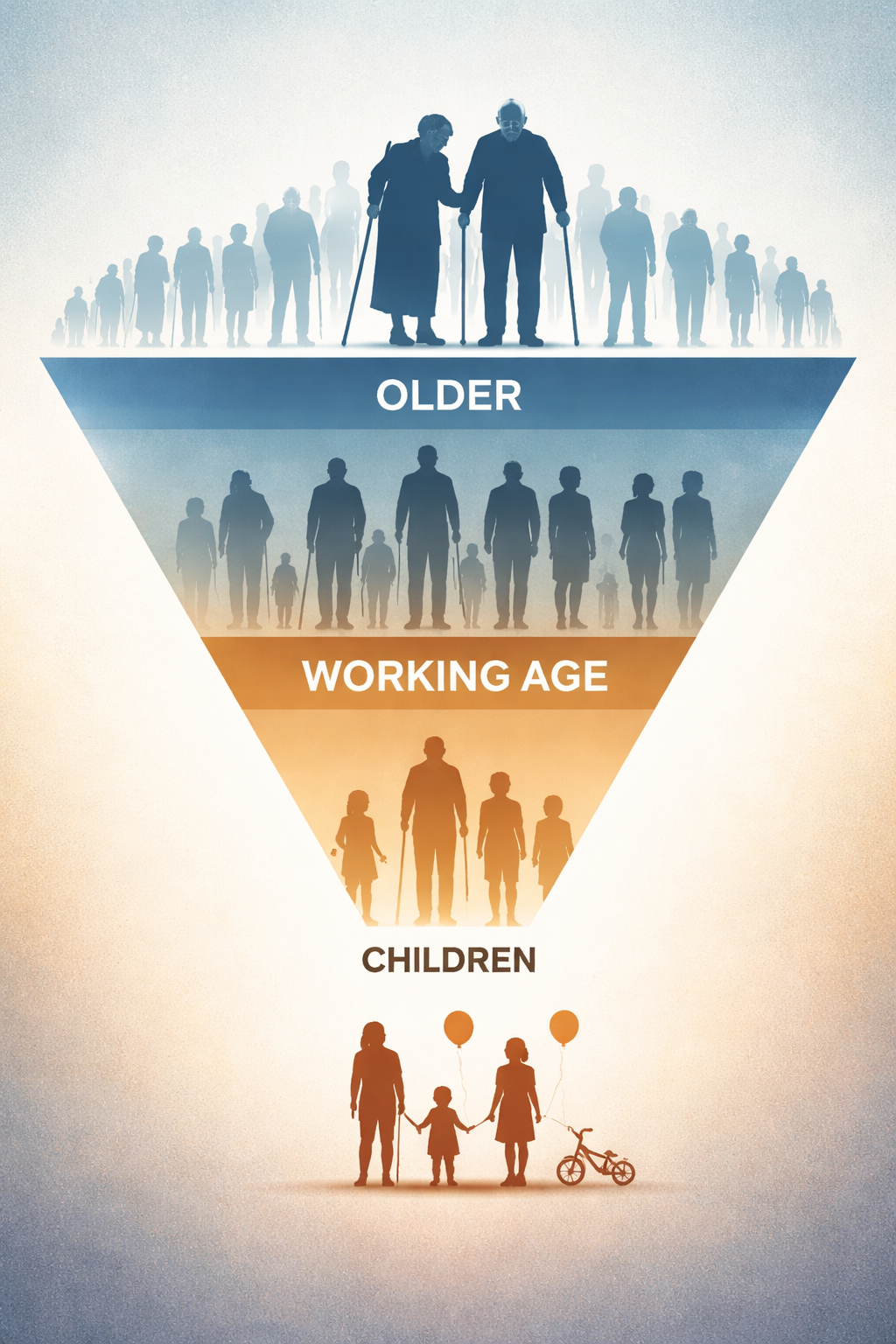

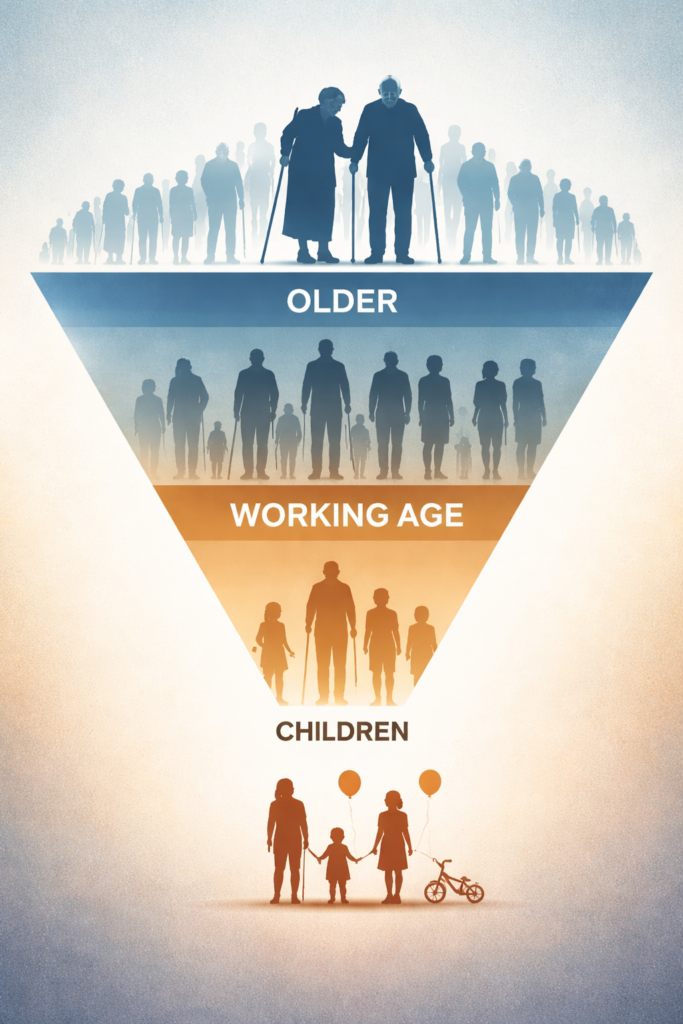

For a long time, societies relied on a simple, almost comforting image: the population pyramid. A wide base of children. A narrowing middle of workers. A small peak of elders. It looked stable, predictable, almost moral. Grow up. Work hard. Rest at the end.

That shape wasn’t an accident. It was the mathematical backbone of modern states. Schools made sense because there were many children. Pension systems worked because there were many workers. Healthcare scaled because fewer people lived long enough to need it extensively.

The pyramid wasn’t just a graph. It was an unspoken promise.

When the Pyramid Starts to Flip

Now that promise is quietly expiring.

In many countries, the base is shrinking while the top grows heavier. Fewer births. Longer lives. The shape tilts upward, like a structure designed for another climate.

Here’s the single hard anchor worth stating clearly:

According to the United Nations World Population Prospects, 2022 revision, by 2050 people aged 65 and older will outnumber children under 15 globally for the first time in recorded history. Institution: United Nations. Year: 2022.

That’s the data. Everything else is consequence.

Why This Isn’t Just a Demographic Issue

It’s tempting to treat aging as a problem for economists, demographers, or policymakers. That’s convenient. It keeps the discomfort at arm’s length.

But the inversion of the age pyramid rewrites everyday assumptions. It reshapes neighborhoods, job markets, family dynamics, and political incentives. It changes what stability means.

A society with fewer children behaves differently even before anyone notices the statistics. Streets get quieter. Risk tolerance drops. Institutions become conservative, not by ideology, but by age distribution.

Older populations don’t crave disruption. They crave continuity. That’s not a flaw. It’s biology with voting rights.

The Subtle Political Gravity of Aging Societies

As populations age, political gravity shifts. Not because anyone planned it, but because numbers vote.

Policies start favoring preservation over experimentation. Budgets lean toward healthcare and pensions rather than long-term infrastructure. Electoral incentives reward caution.

This doesn’t mean decline. It means friction.

Young generations become numerically smaller, louder online, but structurally weaker. Their demands sound urgent, sometimes desperate, precisely because they’re negotiating with systems built for a different demographic era.

The tension isn’t ideological. It’s arithmetic.

Work Stops Being a Phase

One of the quiet casualties of the inverted pyramid is the idea that work has a clean beginning and end.

The old model assumed a short education, a long career, and a brief retirement. That only worked because life expectancy, productivity, and population growth aligned just right for a few decades.

That alignment is gone.

In aging societies, work stretches. Not always by force, but by necessity and sometimes by choice. People stay active longer, not because they love spreadsheets, but because relevance feels better than waiting.

Retirement, once framed as a reward, starts to resemble a pause button that nobody is quite sure how to press anymore.

The Psychological Shift Nobody Talks About

Here’s the part charts don’t show.

When fewer children are born, time feels different. The future feels narrower, not shorter. There’s a sense that fewer people are coming to replace what exists now. That awareness changes behavior.

People become careful. They save more. They hesitate longer. They defend what they built.

Innovation still happens, but it has to negotiate with accumulated experience. That’s not bad. It’s heavier. Progress gains weight.

Families Grow Vertically, Not Horizontally

Another quiet transformation shows up inside homes.

Families shrink sideways and stretch upward. Fewer siblings. More grandparents. More responsibility concentrated on fewer shoulders.

Caring becomes a central economic function, often unpaid and underestimated. Middle-aged adults find themselves supporting both children and parents, squeezed in a demographic vise that wasn’t part of the old script.

The pyramid flips, and suddenly the middle feels thinner than it used to.

This Is Not a Crisis. It’s a Rewriting.

Calling this a crisis misses the point. Crises explode. This doesn’t.

This is a rewrite of expectations, happening slowly enough that denial feels reasonable. But slow doesn’t mean harmless. It means permanent.

The inverted age pyramid doesn’t ask whether systems are ready. It simply waits for them to adapt or strain.

When Longevity Stops Being a Gift and Becomes a Skill

Pensions Were Never About Old Age

There’s a comforting misunderstanding around pensions. People talk about them as if they were rewards for endurance. Work long enough, survive long enough, and the system takes care of you.

That was never really true.

Pension systems were mathematical agreements built on one assumption: many workers would exist for every retiree. That assumption held for a short historical window. A very short one.

As the age pyramid inverts, pensions don’t collapse overnight. They stretch. Rules change. Expectations adjust downward. The system doesn’t break loudly. It renegotiates quietly.

The uncomfortable truth is this: pensions were designed for demographics we no longer have. Treating them as a guaranteed destination rather than a safety floor is a category error.

Longer Lives Demand Longer Usefulness

Aging societies expose a cultural blind spot. We learned how to live longer before learning how to stay useful longer.

Longevity without participation creates pressure. Longevity with participation creates value.

That participation doesn’t have to look like forty hours a week or lifelong careers. It looks more modular. Project-based. Advisory. Remote. Sometimes informal. Sometimes invisible to statistics but essential to social glue.

Inverted pyramids reward people who can keep contributing without pretending to be young. Experience becomes an asset again, not nostalgia.

The irony is obvious if you squint a little. Societies that once rushed people out of the workforce now quietly hope they’ll stay a bit longer.

Productivity Is No Longer About Speed

In younger societies, productivity often means output per hour. Faster. Louder. More.

In older societies, productivity changes character. It becomes about reliability, judgment, error reduction. The kind of work that prevents disasters rather than creating fireworks.

That shift doesn’t show well in headlines. It shows up in fewer mistakes, steadier institutions, and slower but more deliberate change.

There’s a reason older teams tend to break less often. They’ve already seen what breaks.

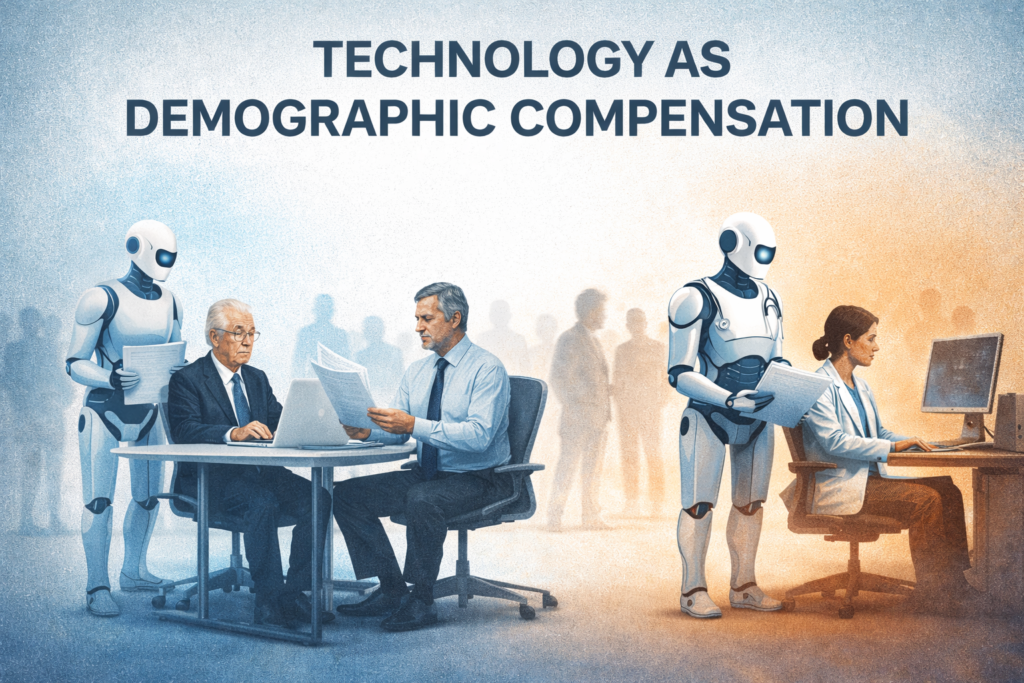

Technology as Demographic Compensation

Here’s where technology enters the story without heroics.

Automation, artificial intelligence, and digital systems are not just tools of efficiency. They’re demographic compensations. When fewer young workers exist, systems look for leverage elsewhere.

Machines absorb repetition. Software absorbs coordination. Humans focus on supervision, context, and decision-making.

This is not about replacing people. It’s about stretching capacity when population growth no longer does the job for free.

Aging societies don’t adopt technology because it’s fashionable. They adopt it because arithmetic leaves no alternative.

The Individual in an Aging World

For individuals, the inverted pyramid quietly rewrites the rules of personal strategy.

Stability stops being about holding one position for decades. It becomes about maintaining optionality. Skills that transfer. Health that sustains. Finances that don’t depend on a single promise.

The most valuable asset in this environment isn’t brilliance. It’s continuity.

People who can keep showing up, learning incrementally, adjusting pace without exiting the game entirely, gain disproportionate advantage. Not because they’re exceptional, but because fewer people are able or willing to do it.

In a long life, consistency compounds quietly.

Health Becomes Economic Infrastructure

One of the least romantic realizations of an aging society is how directly health converts into economic freedom.

A healthy body expands choices. A fragile one narrows them fast.

This doesn’t turn life into a fitness cult. It turns basic maintenance into strategy. Sleep, movement, prevention. Boring habits suddenly outperform clever plans.

The inverted pyramid doesn’t reward heroics. It rewards maintenance.

Families as the New Safety Net

As formal systems stretch, informal ones regain importance.

Families, communities, and local networks quietly take on roles once handled by centralized structures. Care flows upward and downward at the same time. Support becomes reciprocal rather than linear.

This isn’t regression. It’s adaptation.

In aging societies, resilience becomes relational. People embedded in networks cope better than those optimized for independence alone.

The future looks less individualistic than the past promised, even if we pretend otherwise online.

A Different Kind of Growth

There’s a reflex to associate aging with decline. That reflex confuses expansion with progress.

Growth in an aging society doesn’t mean more people. It means better alignment. Smarter use of time. Fewer wasted cycles. Less tolerance for systems that leak energy.

It’s slower. It’s heavier. And strangely, it can be more humane.

An inverted pyramid forces societies to confront limits. Limits, inconvenient as they are, often produce clarity.

Short and Honest Ending

The age pyramid is flipping whether we approve or not.

Systems will adjust. People will adapt. Some expectations will quietly disappear.

This isn’t the end of vitality. It’s the end of automatic renewal.

A longer life isn’t a problem to solve.

It’s a responsibility to manage.

And handled well, it can still be a very good deal.

There’s a reflex to associate aging with decline.

That reflex confuses expansion with progress.

Growth in an aging society doesn’t mean more people.

It means better alignment. Smarter use of time. Fewer wasted cycles. Less tolerance for systems that leak energy.

It’s slower. It’s heavier.

And strangely, it can be more humane.

An inverted pyramid forces societies to confront limits.

Limits, inconvenient as they are, often produce clarity.

This ebook was written for those who want to think clearly inside that reality.

Not to predict the future, but to understand the structure we’re already living in and make better decisions within it.

👉 https://go.hotmart.com/B103519504F

Some ideas aren’t urgent.

They’re structural.

Lizandro Rosberg

Independent analyst of technology, science, and civilizational transformations. He writes about artificial intelligence, science, applied history, the future of work, and the real impact of technology on human life. His focus is on translating complex changes into practical understanding.

You will certainly be interested in:

-

21st Century Economy | Artificial Intelligence | Future of Work | Future of Work & Automation | Life Strategy

The World Is Too Old to Run on Yesterday’s Assumptions

Modern societies are aging faster than their institutions, cities, and care systems were designed to handle. Population aging is no longer a forecast. It is a present condition. Fertility rates across developed economies remain structurally below replacement, while life expectancy continues to rise. More people stay in the system for longer, and fewer enter it to sustain what that system demands. This is not a moral debate. It is arithmetic.

The text dismantles the idea that declining birth rates can be reversed through incentives alone. Children have ceased to be a default continuation of life and have become high-risk projects, requiring time, stability, and energy. At the same time, large cities have grown expensive, regulated, and hostile to family formation. Housing costs, long commutes, and constant friction quietly discourage long-term planning. Fertility declines not because people reject families, but because the environment makes them fragile bets.

Longevity adds a second layer of tension. Medical and technological progress has extended human life by decades, but social structures have not adapted accordingly. Families are smaller, communities weaker, and informal care networks thinner. Care, once distributed among many, now concentrates on a few, often exhausted individuals. As demand rises and supply stagnates, eldercare becomes a systemic bottleneck.

At this point, the article reframes technology. Automation, AI, and robotics are not replacing human care. They are filling gaps left by demographic reality. Safety automation, assisted living systems, and care-support technologies emerge as infrastructure, not luxury. The comparison between regions is telling. China treats automation as capacity planning, scaling solutions pragmatically under demographic pressure. Europe, despite facing even sharper aging trends, often responds with moral discourse and procedural delay. The United States sits between these poles, still assuming it has time.

The article closes without apocalypse. It argues for early, practical adaptation. Designing homes and cities that reduce risk. Introducing assistive technology before crisis. Treating care as infrastructure rather than a private afterthought. Building redundancy not only in finances, but in human networks.

The final note is sober but constructive. The world did not become colder. It became older. And older societies need smarter designs. Less nostalgia. More alignment. In that sense, adapting early is not pessimism. It is a form of responsibility, and perhaps the most realistic kind of optimism available.

-

The Mistake That Kept Rome Standing for Centuries

At its height, the Roman Empire controlled millions of square kilometers and governed tens of millions of people. Some estimates place that peak at over four million square kilometers and roughly 60 million inhabitants, a scale that’s hard to visualize without modern maps.

-

Personal AI for Finances: How Language Models Help You Stop Losing Money

When finances are reviewed regularly, without drama and without emotional drain, something subtle happens. Anxiety drops. Decisions stop being reactive. Small corrections happen early, before they turn into damage.

-

The Rat Race Was Designed, Not Chosen

Most people never sit down and choose a life of constant pressure. They don’t decide to trade freedom for anxiety or flexibility for fragility.

-

Big Cities Have Become Too Expensive for What They Offer

Dense environments demand continuous cognitive processing. The brain never truly rests. It just reallocates priorities. Over time, that state extracts a price. Less patience. Less depth. Less tolerance for error.

-

The Industrial Revolution Didn’t Destroy Jobs. It Stripped Away Illusions.

Modern automation, especially software-driven automation and AI, is hitting symbolic professions first. Not the poorest. Not the wealthiest. It’s hitting the middle layer that learned to trade intellectual routine for stability.