The World Is Too Old to Run on Yesterday’s Assumptions

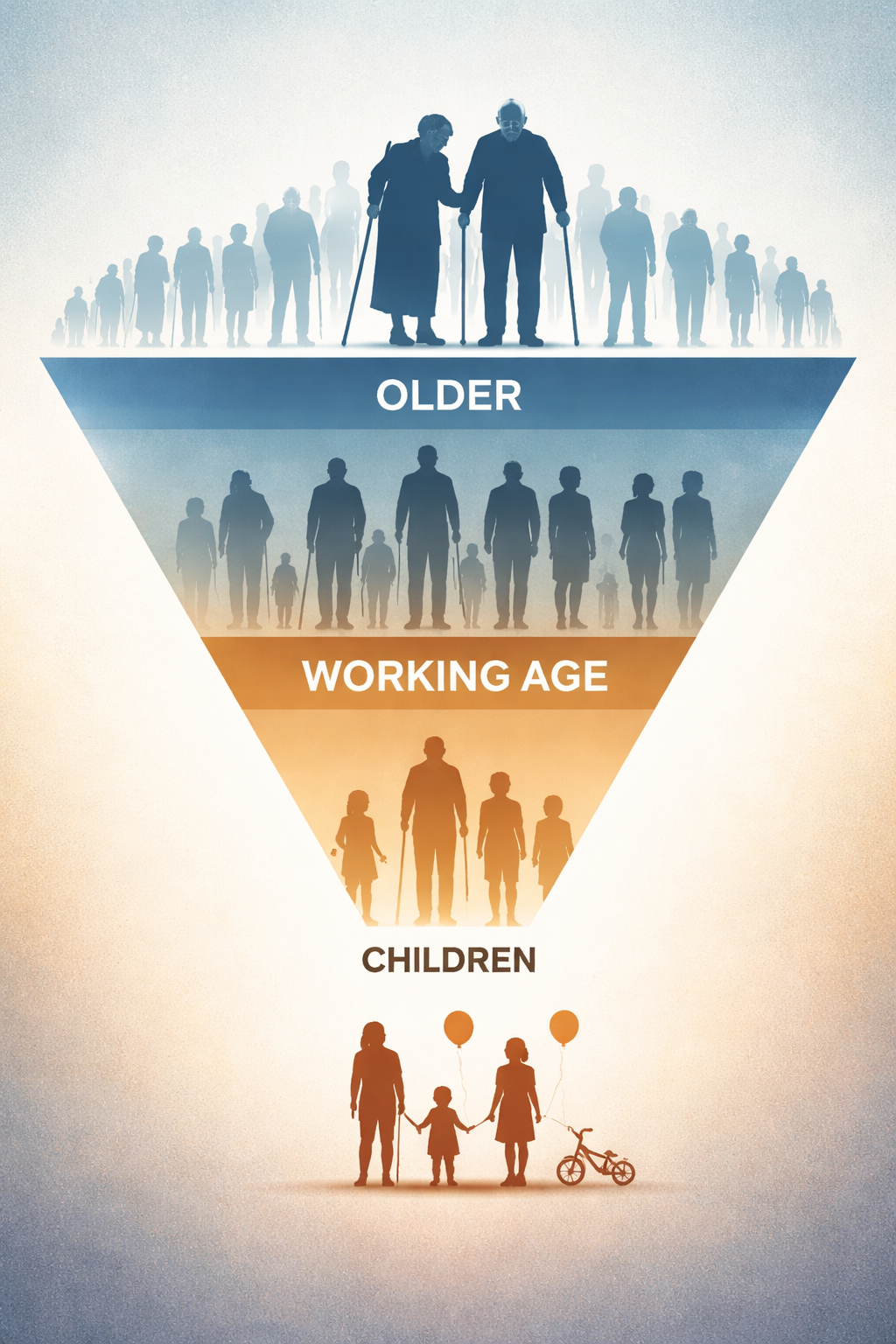

Modern societies are aging faster than their institutions, cities, and care systems were designed to handle. Population aging is no longer a forecast. It is a present condition. Fertility rates across developed economies remain structurally below replacement, while life expectancy continues to rise. More people stay in the system for longer, and fewer enter it to sustain what that system demands. This is not a moral debate. It is arithmetic. The text dismantles the idea that declining birth rates can be reversed through incentives alone. Children have ceased to be a default continuation of life and have become high-risk projects, requiring time, stability, and energy. At the same time, large cities have grown expensive, regulated, and hostile to family formation. Housing costs, long commutes, and constant friction quietly discourage long-term planning. Fertility declines not because people reject families, but because the environment makes them fragile bets. Longevity adds a second layer of tension. Medical and technological progress has extended human life by decades, but social structures have not adapted accordingly. Families are smaller, communities weaker, and informal care networks thinner. Care, once distributed among many, now concentrates on a few, often exhausted individuals. As demand rises and supply stagnates, eldercare becomes a systemic bottleneck. At this point, the article reframes technology. Automation, AI, and robotics are not replacing human care. They are filling gaps left by demographic reality. Safety automation, assisted living systems, and care-support technologies emerge as infrastructure, not luxury. The comparison between regions is telling. China treats automation as capacity planning, scaling solutions pragmatically under demographic pressure. Europe, despite facing even sharper aging trends, often responds with moral discourse and procedural delay. The United States sits between these poles, still assuming it has time. The article closes without apocalypse. It argues for early, practical adaptation. Designing homes and cities that reduce risk. Introducing assistive technology before crisis. Treating care as infrastructure rather than a private afterthought. Building redundancy not only in finances, but in human networks. The final note is sober but constructive. The world did not become colder. It became older. And older societies need smarter designs. Less nostalgia. More alignment. In that sense, adapting early is not pessimism. It is a form of responsibility, and perhaps the most realistic kind of optimism available.

The Industrial Revolution Didn’t Destroy Jobs. It Stripped Away Illusions.

Modern automation, especially software-driven automation and AI, is hitting symbolic professions first. Not the poorest. Not the wealthiest. It’s hitting the middle layer that learned to trade intellectual routine for stability.

Highly Qualified, Quietly Poor

This morning was unremarkable. I made coffee the same way I always do. Same mug. Same […]

The First Robot in Human History

From Talos to the Age of Artificial Intelligence This morning I did something completely ordinary. I […]

We Are Entering the Decade of Augmented Intelligence

When we talk about technology and the future, we are not imagining science fiction. We are describing patterns that repeat across history. Every time a breakthrough changes how humans produce, decide, and interpret reality, a new civilizational chapter begins.

The New Industrial Race Is Not About Factories. It Is About Complete Chains

Factories aren’t the real battlefield anymore. The future of power is decided in invisible chains: energy, data, logistics, and resilience under stress. This article explains why nations that master continuity will outlast those chasing headlines.